During my parents’ first three years of marriage they were anticipating a life overseas with the Foreign Service of the U.S. Department of State, where my father was being trained.

In the spring of 1954, my maternal Grandmother Rathbun arrived at the Pimmit Hills house of George and Eloise in Falls Church, Virginia, to meet her new grandson (I still have that mid-century modern teak desk).

My father’s parents arrived to meet the new Walsh family member in June 1954 (with my parents’ first car presumably in the background):

Within a year after I was born my father started shooting 16mm home movies, the format without sound that had been upstaged 20 years earlier by 8mm film with sound, which presumably was also more expensive to buy and/or process than 16mm. I recently uploaded an 18-minute video of several movies he shot between 1954 and 1965, from the first of two batches of movies that my brother Frank discovered in our mother’s basement in late 2016. Unfortunately, the movies are not in chronological order, since it was impossible to determine beforehand the proper order when transferring the unmarked movie reels to DVD, and I haven’t yet learned the editing tools on YouTube. (This was my first-ever video upload.)

My father shot his first movie at my first home, as can be seen in the link below. The contents of the 18-minute video:

- Me as a baby, my mother, my paternal grandmother Clyda and grandfather Michael (“Mickey” as his wife sometimes called him)

- 1962-64 in Pakistan, showing me and my siblings (Frank and Louisa), my mother, our chief Pakistani “bearer” (domestic employee) Kulinder Khan

- 1956 in Darjeeling, India, showing at various times some Tibetan monks and their textile industry

- Chinese Premier Chou En Lai in his motorcade in Calcutta, my father’s first overseas assignment

- softball game in Calcutta, presumably involving U.S. Consulate personnel

- sparklers in Calcutta during some unknown celebration, probably July 4th

- our trip from Calcutta to Darjeeling showing Mt. Everest, my father and mother, me and my nanny Mary, and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, who had just climbed Everest with Sir Edmund Hillary only three years earlier

Walsh Home Movies 1954 to 1964: Arlington, India, Pakistan

In San Francisco, while en route to our Calcutta post in the summer of 1955, we stopped to visit my maternal uncles Stan Rathbun, Alvin Rathbun and his wife Ginny and children Victoria and Susan, as well as my maternal aunt Jean Rathbun and her husband Ken Conningham and children Lawrence and Eric.

“New Year’s Eve at Firpo’s,” Calcutta, Dec. 31, 1955, four months after arriving in country:

More parties in Calcutta, 1956:

“India – 1955-1957″…

The following shows home life in Calcutta and my parents exploring India and Thailand (dates and sequence unknown):

My earliest memories are of our house and neighborhood in Calcutta. I remember riding in rickshaws and looking over the balcony that is shown in the photo in which a servant is carrying me on the patio below. Family lore alleges that my first language was Bengali and my staple diet as a two-year-old was Indian curry that the servants would make for themselves in their quarters, the door to which can be seen in the same photo.

Our house balcony also gave a view to the neighbor’s compound, which was the scene of an Indian religious holiday involving a sacrifice. I don’t think my parents knew that I was at the balcony alone when I saw the neighbor’s servants slit their goat’s throat and spill its blood on the ground. I was about three years old.

As Calcutta was my father’s first overseas post, he was a junior officer and would most likely have served as a vice-consul manning the consulate window at which U.S. visa applicants would line up to be interviewed. The look and amenities of our house appear to be consistent with Government-leased quarters (GLQ) likely to have been provided to junior officers in Calcutta at the time.

Other amenities provided to U.S. Consulate personnel in India would have included membership to an exclusive swimming club nearby.

At the swimming pool in Calcutta:

Trip to Darjeeling November 8-16, 1956, with Mt. Everest in the background of some shots:

Watching and holding sparklers at night during a celebration is also among my earliest memories, along with walks to the local park with Mary, my nanny (aya in Bengali). The park had a see-saw and a round platform that Mary would twirl while I rode on it. I also remember walking home with her and passing a gate with wide gaps between the iron bars, behind which a dog barked and lunged at me, a dog that looked as big as a horse. It had the markings and color of something wild, like a hyena. It scared the hell out of me.

Mary would certainly have calmed me about that dog. My parents always spoke with the highest praise about her. Mary was a Christian, as her name suggests. Christians in that region (West Bengal) accounted for about 1 percent of the population, but Mother Teresa was already well established in Calcutta, so they were a famous 1 percent. My parents kept several promotional photographs and souvenirs of Mother Teresa’s mission there.

Family lore includes one anecdote about Mary’s devotion to my well being and entertainment: She used to catch butterflies and tie a thread to them so I could hold them with the thread as they flew around.

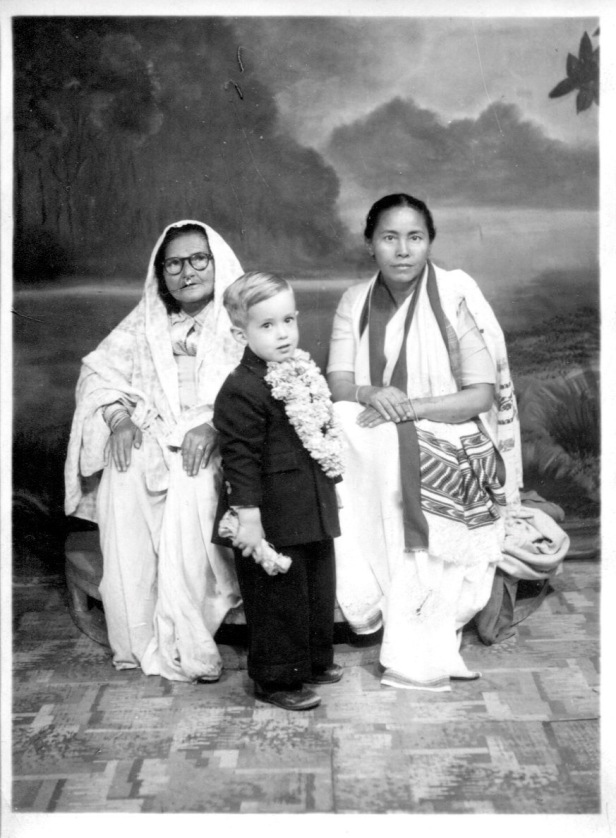

An ex-pat and an unknown (temporary?) nanny in India (Darjeeling?), 1955-1957:

Calcutta costume party, Saturday, March 2nd, 1957:

Calcutta, March-June, 1957:

In the summer of 1957 the Walsh family departed Calcutta, as my father was reassigned to the U.S. Embassy in Colombo, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). We flew from India to Washington, D.C., and Boston for home leave, then to San Francisco, where we boarded the S.S. President Polk in late August 1957, westbound across the Pacific. Our destination was Colombo, but the ship was on a round-the-world voyage, New York being its final stop…

I remember making friends with the bartender, who had a mechanical monkey that dispensed drinks (Coke, in my case). I remember the pool well, too.

But family lore has me almost dying twice on that ship: Once when I slipped through the safety ring in the pool, prompting my father to jump in and save me, and once when I got very sick with a high fever, and the ship’s doctor was unable to treat me very well. After I recovered in a few days, I allegedly ate only butter for the rest of the voyage. Our last dinner on the ship was on September 2nd, 1957, when we arrived in Colombo. The menu:

I assume my parents indulged themselves, even if I would eat only butter.

In Ceylon, Sept. 1957 to Aug. 1960:

At the end of our first year in Colombo we flew back to Washington, D.C. for R&R (rest and relaxation), or home leave, where Frank was born (and a new passport photo needed him in it):

My sister, however, was born in Colombo two years later. My mother’s notation on the back of one of the following photos: “Louisa Jean Walsh’s first picture, taken on Frank’s 2nd birthday, in Colombo, Ceylon, at 3 ½ months”…

Party at our school in Colombo, c. 1960:

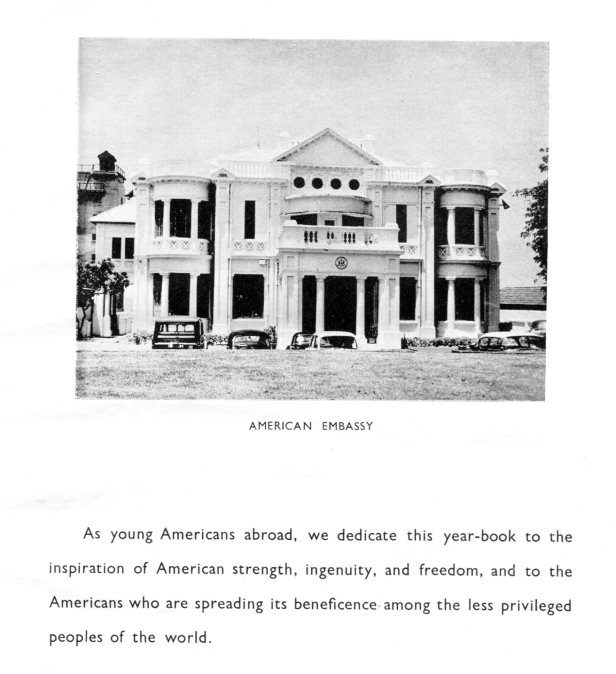

The year from January 1959 to January 1960 was the first year of existence for my school, the American Community Center (ACC), and I still have the first yearbook (The Cobra) that was issued by the school. Its pages have some photos worth posting, including one of the 1960 U.S. Embassy in Colombo, where my father worked:

I remember being in my father’s office often. It had the pleasant smell of tea-leaves, with straw mats on the floor, and the charm of an old, stately residence, which it probably had been at one time. It’s quite a contrast to the embassy that stands now, and today (Dec. 6, 2016), they broke new ground to expand it further. I remember seeing the official portrait of President Eisenhower and then President John F. Kennedy on the wall of my father’s workplace. The portrait has been replaced nine times since then.

At least for a few months, the U.S. Embassy provided an official government vehicle (OGV) and a local driver employed by the embassy to transport me to and from school. I learned much of the local language (including some bad words) from that driver, who also allowed me to handle the gearshift on the floor of the black Jeep Wagoneer (or similar), which I learned to shift whenever his foot depressed the clutch pedal. I joined the Cub Scouts in Ceylon, and I also seem to remember that embassy vehicles took me to Scout meetings as well. Today, USG rules restrict personal use of OGVs except in dangerous conditions.

Well, arriving home from school in that Jeep became dangerous. On Easter 1960, my parents hid a bunch of baby chickens (6-8?) in a shallow basket, covered with a cloth napkin, for Frank and me to find in the morning. Frank, not yet two years old, was the first to find them, and was experimenting with color as a future artist. My parents were horrified to discover him sitting near the basket, covered in chicken blood, with a look of blissful wonderment on his face. Two of the chicks survived Frank’s tactile fascination and one grew up to be a rooster, and we soon had fresh eggs daily among the growing chicken population. When the rooster started crowing, I imitated him, and he soon came to view me as a rival, and would attack me every time he saw me. He learned to stand vigil at the gate, and when I arrived home, the driver would have to block the rooster’s view with the Jeep so I could dash into the front door and avoid my attacker.

After the Easter Massacre, my parents gave that rooster a reprieve, despite his attacks on the young master of the house. But the fowl’s days were nevertheless numbered. One evening, my mother was stunned to find the rooster plucked, trussed up and cooked in a saucepan. The cook had confused my mother’s instructions to prepare and serve the duck for a dinner party that night. End of dangerous arrivals for Master Michael.

In the spring of 1960, my father took me for a few weeks to Srinagar in Kashmir, and we stayed on a houseboat on Dal Lake, as in the movie Passage to India. We also went horseback riding and fly-fished in a river.

In 1959-60, the Chairman of the Executive Board of the American Community Center was Mr. C. William Kontos, whose son, Stephen, was one of my best friends. I used to play at his house a lot, where I first learned about Tonka and Matchbox toys. (I was very impressed with his two favorite Matchbox cars, a silver-blue Chevrolet Impala and a cream Ford Thunderbird, which he would allow me to handle sometimes.) Our neighbors were the Kriegel family, with two brothers named Bobby and the younger Skippy, a friend who loaned me his bicycle to learn how to ride without training wheels. My father was then prompted to buy my first bicycle, a red Raleigh with chrome accents, which can be seen in the home movies and in the Walsh group photo above.

The Cobra, 1959-1960:

Three years later, Bobby Kriegel, Mark Smith (then a freshman at ACC) and Colombo resident Arthur C. Clarke discovered the Taj Mahal Sunken Treasure while scuba-diving in the Indian Ocean, documented in Clarke’s book titled Treasure of the Great Reef. My father taught me to swim at the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo, and took me snorkelling in the Indian Ocean, and I remember admiring Bobby’s reputation for ocean sports.

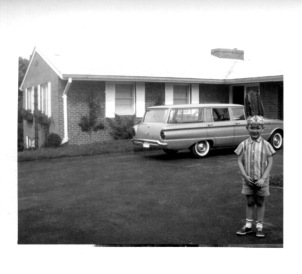

The Walsh family left Colombo in the summer of 1960 when my father was reassigned to Washington, D.C. We rented a house in Arlington, Virginia, while my parents searched for a house to buy. My mother found the one she wanted, even though it was still under construction, and by the fall we moved in as it was still being landscaped…

6661 Sorrel St., McLean VA, 22101. Ph. 356-3974. (No area code in 1960.)

Michael’s 8th birthday…

In those years my father assigned me chores to earn my allowance of 25 cents per hour: Mow the lawn and take out the trash. That could account for the poor state of the lawn showing n the above photos, but I do remember my father having me use a wheeled fertilizer applicator at least once.

The school bus picked me up every weekday to go to Churchill Road Elementary School for 2nd, 3rd and 4th grades. At age eight I used to walk back home in the fall and spring, and stopped along the way home for swimming practice at a private home half-way up Ingleside Ave. The route took me 1.4 miles one-way. Gordon, who was seven, and I used to walk about the same distance down Pine Hill Rd. to reach Salona Village in the center of McLean to buy toys. We’d also walk up Whann Ave. in the winter to play on the ice on Dead Run, back when the creek would freeze over regularly. On Halloween, we older kids (age 6-8) would trick-or-treat all around the neighborhood alone at night. It was wonderfully spooky. It was a different world back then.

Over a few weeks my father corrected my shortfall in multiplication tables. He used flashcards to get me up to speed. Our routine was to sit on the brick hearth of the fireplace for flashcard drills, and it did the trick.

In the summer of 1963 the Walsh family left D.C. for Rawalpindi, Pakistan, and rented out our McLean house for the next six years.

On the way, we stopped in San Francisco to visit family:

Since we moved a lot, and making new friends was not easy until school started, we siblings often played with each other, especially Frank and me. One favorite activity was building cityscapes in a bedroom using flat chair cushions for the foundation, with the gaps between the cushions serving as canals. We got pretty elaborate with bridges, roads and makeshift facilities commonly found in model train sets, like fire stations and post offices. We also dug covered forts in the back yard and conducted military operations. These activities eventually gave way to playing softball in the back yard with my school friends, and converting our lift-van crate into a clubhouse in another part of the yard, which was amply sized for such variety of activity. (I don’t recall if my siblings were club members.)

Our next-door neighbor was the Mir of Hunza and his family, and I sometimes played with his son. My father installed a U.S.-imported basketball hoop over our garage door and I occasionally shot hoops with the Mir’s son, who didn’t speak a word of English. Another boyhood friend of mine was the French ambassador’s son, who taught me chess. He also didn’t speak English and I didn’t speak French, but we enjoyed our games.

Life in Pakistan, 1963-1966:

Costume parties in Rawalpindi:

Rawalpindi production of “The Fantasticks” featuring George Walsh, Anthony Quainton and Eric Foster:

I was in the audience and remember that performance well. My impression was that Tony Quainton played the Mute with appropriate, emotionless understatement, and my father and Eric Foster (an Englishman with the Native American headdress) played their roles with equally appropriate overstatement. Everyone seemed to be perfectly cast, and I was enthralled. (We had no television in Pakistan.)

At the Fleischmann Hotel, probably the only place in Rawalpindi that served alcohol to foreigners at that time (now called the Flashman Hotel), my father performed in at least two other ex-pat productions for the local and diplomatic audience. One was a monologue, his rousing rendition of Casey at the Bat, which brought the house down, and the other was a dramatic reading of A Christmas Carol in which he involved me: Towards the end of this reading, he had me waiting in the hotel’s kitchen, dressed as a street urchin and holding a live turkey (or a reasonable Pakistani version of one) in my arms. At the moment when Scrooge called for a local boy to bring him a turkey for Tiny Tim’s family for Christmas dinner, I ran out to the podium with the struggling turkey in my arms, duly showing how out of breath I was after running so far and fast with the turkey for the sake of the shilling that Scrooge had offered me. It caused a sensation in the audience, as I recall.

Scenes in Rawalpindi, Murree, and on a boat en route to the countryside:

Since we had no television or English language radio in Pakistan (except the BBC on short wave radio), we spent a lot of time reading books and comics and listening to records (LP and 45 RPM). Frank also spent a lot of time drawing. The living room in our Rawalpindi house was the quintessential scene of domestic tranquility, with parents on the couch reading news, poetry and history, three kids sprawled on the rug while reading or drawing, and all listening to our bliss through the Sherwood vacuum tube amplifier (minus cover), KLH bookshelf speakers sitting on the floor, and the Garrard turntable, all of which my father bought as a package in 1960 at Shrader’s Sound (“the first good stereo store in DC“) on Wisconsin Avenue in Georgetown.

We siblings are thankful for our parents’ eclectic taste in music, which included a wide range of classical (operas, symphonies, chamber and choir music) as well as folk, jazz, Gilbert and Sullivan, Broadway hits and movie soundtracks. A few recordings stand out as favorites that we still invoke occasionally: Amahl and the Night Visitors at Christmastime, and a multi-record album of Cyril Ritchard reading the whole story of Alice in Wonderland, most of which we kids learned by heart, with voice changes for characters included.

My first awareness of the charm and grip of U.S. popular music was in Rawalpindi. My best friend, George Holmes, whose father worked for the Ford Foundation, lived only a half-mile from us, and I often played at his house. His older sister Peggy used to listen to 45 RPM records of Top 40 hits like Johnny Angel, and a song by Brian Hyland that blew my mind. One of my parents’ friends from the office loaned me an Elvis record, which hooked me for months before my father bought me my first pop LP, the Beatles’ Please Please Me, which further altered my popular music consciousness, and there was no turning back.

We did see some Hollywood movies in Pakistan. The small U.S. military installation where our school was first located showed movies in one of the quonset huts. The Longest Day and Son of Flubber and That Darned Cat! come to mind. We also remember seeing a few English-language movies in local theaters, including one that Dad endorsed since it starred John Wayne and Jimmy Stewart (The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,) and “Hercules Unchained” starring Steve Reeves. They had Urdu subtitles, and before the movie started the audience, including foreigners, had to stand and sing the Pakistan national anthem, so Frank and I still remember the tune, and the obligatory shout “Pakistan zindabad!” (Long live Pakistan!) at the end.

Other activities we sometimes did on weekends (Friday and Saturday for Americans living in a Moslem country) included hunting duck and partridge, rock-hunting, fossil-hunting, and camping. My father gave me a .410 .22 “over-under” combination shotgun-22, which I used on hunting trips while my parents used the more powerful 12-gauge shotguns. My father used to take me target-practicing in the nearby dusty, barren hills of the future Islamabad, where I would shoot tin cans with the .22 caliber.

I remember waking up early one Friday in November, excited to be heading out on a camping trip, only to find my parents in the living room, my mother crying. They told me President Kennedy had been shot. I could see how upset they were, and realized it was a grave moment, but just to be sure, I asked if that meant we weren’t going camping. I was ten. On a hunting trip weeks or months after that, I was in a boat on a lake with my parents and shooting a duck that was flying overhead, which fell dead in the lake. We rowed over to reach the dead duck floating in the water, and when I saw it close-up I had an epiphany. I refused to eat the duck for dinner and never went hunting again.

I joined the Boy Scouts and raised pigeons on our roof (and in the lift-van crate that I’d converted into a clubhouse) for a Merit Badge in animal husbandry. I often rode my bike alone to the local market a couple of miles away to shop for pigeons, bringing them back in a cage on the rear rack of my bicycle. Such solo excursions also took me to a Pakistan Air Force graveyard, where I explored the rusting carcasses of DC-6 military transport aircraft. I was an avid builder of Revell model planes and ships, so I was having fun poking around the cannibalized aircraft, but I was discovered once by local boys, and fled on my bike as they chased me through the bumpy dirt field, no doubt because they thought I was a spy from India.

Along with my pigeons, our backyard animals included a resident cat (Puss-in-Boots), a dog that I saved from abandonment on a rooftop of a house under construction on the way to the Holmes house, ducks that occupied the mali (irrigation) pool, and chickens that produced fresh eggs every day (especially Henny Penny and Chicken Little), which shared the converted lift-van clubhouse pigeon coop. And my dog then had puppies, doubling the animal population for awhile. I attribute our relative immunity to bacterial diseases later in life to the fertile environment we played in as kids, with little regard to “germs.”

Our Pakistan tour was not all fun and games. My first school there was not up to standards and my father spent many hours at home helping me with arithmetic word problems until I thoroughly understood such formulas as “speed x time = distance.” The summer heat was stifling, there were frequent earthquakes that sometimes sent us bolting from the house, and fresh food was very limited. My mother got tired of eating chicken, and local fruits and vegetables had to be disinfected for an hour in the kitchen sink, which didn’t always prevent food poisoning anyway. Fresh milk was unavailable, so we drank the powdered stuff called Klim. The embassy commissary was good for limited goods from the U.S. (like Winston cigarettes and cocktail olives for my parents’ party guests), but didn’t have much variety or frozen food. I don’t remember anything I liked from the commissary except ingredients for making cinnamon rolls (which our chief servant Kulinder made well and often) and maybe Log Cabin maple syrup. And even then, my British Commonwealth friends from Canada and Australia had pantries with something exotically British and therefore better, of course: Lyle’s Golden Syrup, which was unavailable in our commissary.

On our long road trip to the mountain kingdom of Swat, my parents underestimated the length of the trip (maybe compounded by a possible breakdown of our car) and we found ourselves critically thirsty, unable to stop and drink any local water for fear of contamination, until we finally found a vendor selling sarda melon, safe and juicy enough to quench us. (Apparently the Coca-Cola Company hadn’t yet penetrated the market in those remote areas.) I’m not sure exactly when, but my mother spent weeks (months?) in bed at our house in Rawalpindi when she contracted acute Hepatitis A from food contamination somewhere.

And rabies was always a worry. Bats and feral dogs were common, and one of my dog’s puppies contracted rabies. Although we had not touched the puppy when it displayed symptoms, our whole family had to go to the embassy clinic every day for 21 days in a row, to get a shot in our stomach with a thick, 6-inch needle and syringe filled with vile-looking, brown-colored serum, which felt very cold when injected because it was just out of the storage fridge. Once a person develops rabies symptoms the disease is usually fatal, so we took no chances, even though none of us had been bit.

By this time, all Walsh family members had been thoroughly stuck with needles by State Department doctors and nurses over the years, every time we transferred to a new overseas post, and again with booster shots in country. We’d been inoculated against Typhus, Tetanus, Typhoid, Polio, Cholera, Hepatitus A, Hepatitus B, etc., etc., and rabies vaccine shots were always among the regimen, and we’d become used to it. But this was different, as all our previous shots were relatively painless, with 2-inch, extremely thin needles, and routinely administered to the upper arm or, occasionally, the buttocks. This time it was a “post-exposure treatment,” different in volume, frequency and intimidation factor by several orders of magnitude. I was ten years old and it was horrible enough for me, so I can only imagine what it was like for my five-year-old brother and three-year-old sister.

My parents finally bought an ice cream maker, which was one of the only home-style culinary treats we could experience. Gordon, my best friend in McLean, would sometimes send small care-packages to me in the diplomatic mail, which included interesting and sentimental items from our times together. For other U.S. imported treats we did take semiannual road trips from Rawalpindi to Peshawar, a half-day drive in those days, where a U.S. Air Force base was located. My parents did all of their Christmas shopping at the Post Exchange (PX) on that base, and that’s where we kids stocked up on records (LPs and 45 RPM) and the latest Marvel and DC comics, as well as the Classics Illustrated comics that our parents favored for us kids. We’d read them all day whenever we stayed at the mountain vacation house in Murree. Badminton was a favorite game at both our Murree and Rawalpindi houses. Benazir Bhutto, who was my age, joined us in those games when her family came to visit. I remember she used to tell tall tales as entertainment. One of them was about a flying snake she called an “ooks snake.” We kids laughed about it, and it was years later that I discovered that one tree snake (not called “ooks,” which may be the Urdu name) can actually appear to fly.

In the summer of 1964 we flew to Greece for a few weeks of R&R:

On October 20, 1964, when the Walsh family was in mid-tour in Rawalpindi, the governor of Kentucky commissioned my grandfather a Kentucky Colonel:

Christmas 1964:

Mountain vacation house, Murree, 1965:

One day in mid-September 1965 my father came home from work and told us to tape up the windows, and he blacked out the top half of the car’s headlights and turned off all the house lights after sundown. That night we slept on the floor of the hallway with no windows, anticipating that bombs would be dropping overnight. It was the start of the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965.

The next morning I awoke to find out that India had indeed bombed our neighborhood, and all my family, except me, was up all night. I had slept through it all, and I was annoyed that no one woke me up for the excitement. (This seemed to be a pattern, as my parents also didn’t wake me when Marlon Brando came to dinner and dramatized his Mutiny on the Bounty scenes, using our antique Afghan musket as a prop. The family lore includes the allegation that Brando, as part of his drama at our house that night, kissed the hostess, supposedly on the lips.)

Two days later, Embassy mothers and kids boarded a U.S. Air Force C-130 cargo plane and were evacuated to Tehran, Iran. My father joined us a month or so later. (Consulate personnel in Lahore were in the same boat, so to speak, and U.S. personnel at the U.S. base in Peshawar were evacuated to Istanbul.)

While the American evacuees were stuck in the Sina Hotel in Tehran, we kids could not roam the city streets, so we made our own entertainment, especially since the only television shows in the hotel lobby that we could stand were My Favorite Martian and Mister Ed, which apparently were broadcast by the U.S. Armed Forces entertainment network, provided by the U.S. military installation in Tehran at the time. Although the Beach Boys’ California Girls was high on our favorites list by now, my pals and I put on a Beatles show on the outdoor stage, complete with cardboard cutouts for guitars, and played 45 RPMs on a portable record player. We handed out fliers a few days beforehand, and sure enough, the bored people of the hotel came to see us play air guitars (we invented the genre, of course). Some in the audience didn’t stay long, of course, but others seemed to be entertained.

We stayed in the Sina Hotel for at least six weeks, which included Halloween, when all the American kids in costumes ran through the halls of the hotel searching for a sign on the doors that promised trick-or-treat participation by the guests. During this hotel stint I was bussed, along with the other kids in the hotel, to the embassy-sponsored American school for the first semester of 7th Grade, where I first started learning geometry, Latin, Farsi (required by Iran) and French (instead of Spanish, due to my father’s preference for the language of diplomacy). I also learned about “slam-books,” the hardcopy precursor to Facebook, discovering what classmates will say about each other in print, which wasn’t always pretty.

After about six weeks in the hotel, a wonderful U.S. military family (the Robies) welcomed us into their home for the rest of our evacuation status, and it was like arriving in the U.S., especially compared to Rawalpindi. They had a swimming pool and a beautiful garden and patio, and their television received all the Armed Forces Network channels, and I was glued to it, watching all the Perry Mason and The Twilight Zone shows that I could in secret, way after bedtime. Frank and I remember one friend of the Robie family had a car with a player installed in the glovebox that played 45 RPMs, without skipping, while the car was in motion. Tehran was an eye-opener for the Walsh kids.

We returned to Rawalpindi in December 1965 to find that our embassy-sponsored school was no longer housed in the old quonset huts on the compound of the U.S. Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), where my schooling for the previous two years had been under the Calvert Education home-school system (with a non-accredited “teacher” to supervise). It had moved into new quonset huts on its own compound. Also, the teaching method had switched from the Calvert system (which did teach me fractions) to the more conventional textbooks found in public schools in the U.S. (or my school in Tehran at the time), with accredited teachers.

There were about four or five students in my new 7th-grade class. One was a new classmate who’d just arrived from the U.S., a striking girl named Debbie Love (no kidding), and I was dazzled. I remember trying to impress her with my knowledge of the Beatles. Her response?

“I prefer the Stones,” she said, smiling, rather dismissively, I thought. I was pretty deflated. I’d never heard of that band, but I figured they must be very sophisticated and radical, and that Debbie was clearly out of my league.

That last semester in Pakistan was a dramatic one for me: Inspired by the marionette scene in The Sound of Music, I constructed a miniature stage on our back patio and put on a puppet show of my own for my family. And I played the greedy king in a musical version of Rumpelstiltskin that was written by the school principal, my first real acting in a school play. Jane Rogers, my puppy-love crush, played the miller’s daughter, and Frank played a king’s court minion in that production. (I still have the original mimeographed lyrics that Jane and I sang.) I was developing a taste for the stage, no doubt from a seed planted by my father. My parents regularly hosted play readings and Scottish dancing, which turned our living room into a hotbed of lively arts. Dad often enlisted my help when preparing to host dramatic productions. I remember one task he assigned me that involved delicately forming a tiny “noose” out of thread and gluing it to a red 35mm transparency, which was used in a slide projector to display an ominous “gallows” on the wall at the right dramatic moment. In his latest book, Anthony Quainton mentioned that their local theatrical group called the RATS, the Rawalpindi Amateur Theatrical Society, had produced Arms and the Man by George Bernard Shaw at my father’s house. I wonder if that noose I made was for that production.

The following photos show our last day at our house in Pakistan, on our way to Cairo via Europe and McLean in June 1966:

My taste in popular music in 1966 tended to lean towards the bubble-gum, love-me-do and surfer-girl kind. My father’s gift to me of Bob Dylan’s breakout 45 RPM, which I also loved, was the anomaly, and its cultural significance wasn’t yet apparent to me. It wasn’t long after leaving Pakistan that I discovered, and fell for, the music of the Rolling Stones when I first heard Paint It, Black playing on the stereo of a new friend’s older brother in Cairo. It was a revelation. And my father, an avid reader of music reviews who often chose music for gifts, contributed to my expanding tastes, but couldn’t foresee all the consequences. He knew good music when he heard it and read about it, but of course he didn’t know the Beatles would be “more popular than Jesus” and banned in Greece.

(See additional blog for more details of the Walsh family’s India and Pakistan tours)

Wow, lot’s of research and work. I like the pop-up captions.

LikeLike

Amazing pictures and narrative. This is an outline for a book! (Do you still like butter?) Eva

LikeLike

LOVE butter!

LikeLike

The resemblance between the first picture of George in the costume party series (costumedad1-1) and his grandson Ian rocked me. Like Paul said in an earlier posting, genetics are fascinating.

LikeLike

Somehow I can’t see George Walsh as a Kentucky Colonel. Regardless of his heritage, he will always be Boston to me.

LikeLike

I agree, so I changed the logo to something more appropriate, which I explain in the final chapter covering 1981-2012.

LikeLike

The time stamps seem off. I see Leo posted Dec. 31, 2016 at 5PM. That would put him in the Atlantic as off 11AM Dec, 2016?

LikeLike

For our last series of rabies shots, Louisa and I convinced the driver, who drove us to and from school, to go the Embassy instead of home. I am surprised now that a five year old and a four year old could convince an adult to sway from his duties but I’ll leave my speculations as to his reasons alone. So, our stomachs had by that time been inured to those wicked needles and I remember the doc was surprised we came in alone. But he stuck us with alacrity and sent us on our way.

Years later, in Cairo, I heard that a schoolmate had been bit by a dog and fearing the shots, convinced his companion not to tell of the incident. Niles Johnson died of rabies after returning to the States soon after. If I had known I would have told him the shots, you get used to them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great stuff, Frank, thanks for the comment! You and Louisa wanted to save time and trouble by combining trips?

LikeLike

Probably. And we wanted to impress Mom with our bravery. Hard to remember. Mom definitely thought we were pulling a fast one telling her, ‘We already went’. She called for confirmation, of course.

LikeLike

LOL, That’s precious!

LikeLike

Ph. 356-3974. Nope. 356-4451. Did you ever hear the story that if you called 356-. . . (don’t remember) you would get the CIA?

LikeLike

You’re right, -3974 was Gordon’s phone number next door.

LikeLike